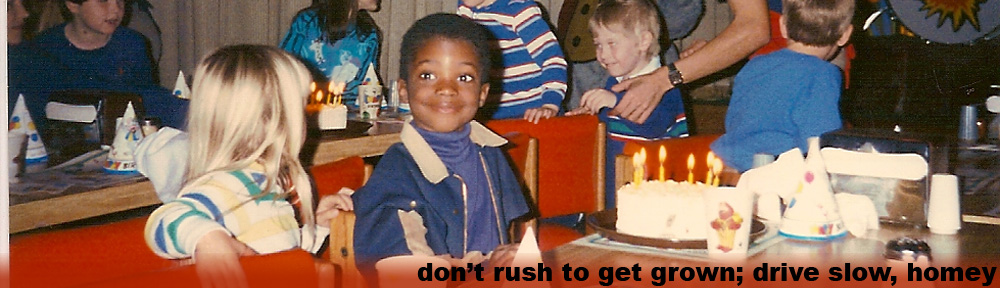

dedicated to All-Negro Comics #1, from the short story collection Darker Than Blue: Go Back and Get It

The ghost wore a green flapper dress straight out of the 1920s and a short hair style that perfectly framed and flattered her full nose and high cheekbones. The green dress provided a perfect contrast with her brown skin and dark eyes, not to mention the red on her lips—a Coca-Cola Christmas shade. She looked for all the world like she stepped straight out of the Harlem Renaissance, forever trapped in a single moment of her life. She certainly looked like trouble, and that’s how Ace Harlem knew he wanted nothing to do with her as soon as he saw her.

Ace noticed her in a corner of his room after he got home from school. She was poking around, looking at all his stuff. It had been another long day of dodging Saul Root and his gang, Ace trying his best not to sleep through the boring classes, and trying even harder not to ruin the curve in the classes he liked. Ace was smarter than anyone he’d ever met, which made life tedious sometimes. He could see what was about to happen long before it actually did, but there wasn’t much a thirteen-year-old boy who stood barely four foot eight could do about anything, outside of taking a different route home to avoid a bully or tanking his grades in certain classes to keep from being looked over just a little too much.

When he got in, he looked at the ghost, blinked at her once, and then immediately looked away as if he hadn’t seen her. She’d been sitting on the floor in front of his closet and sprang to her feet when he walked in. She popped her teeth when he looked away, but he gave no indication that he’d heard or seen her beyond that brief glance.

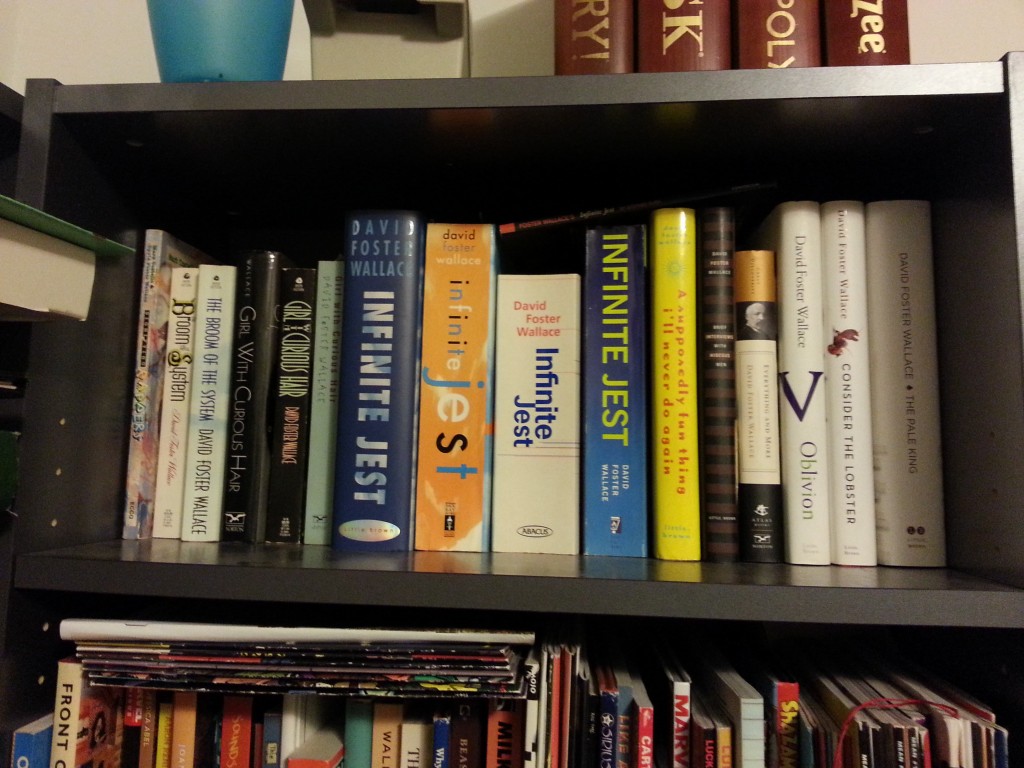

Ace wandered around his bedroom putting away his school supplies, setting his homework out on his bed, and choosing clothes for tomorrow. Tomorrow was Saturday, and he planned to hit the black-owned bookstore a couple neighborhoods over to see what was new and catch up with the owners, the Washingtons. They were good to him, sometimes even letting him read down in the basement for as long as he wanted. He made it a point not to look at the ghost while he puttered around, which only made her want to make it even harder on him.

She started dancing in front of his television, moving her body to a tune only she could hear. It was a jitterbug at first, something Ace knew about thanks to his grandmother. His grandma loved Cab Calloway, and her own mother had kept his records around while she was growing up. Nowadays, she’d play clips from YouTube on her phone for her grandson while they ate dinner on her corduroy couch or on lazy Sundays after church.

The ghost continued to boogie while Ace sprawled on his bed. Grandma always said he had to complete his homework before he played video games, and he was an obedient kid, at least for the most part. He watched the ghost out of the corner of his eye, taking a peek here and there. Even though she was moving without the music and had no partner, he was forced to admit that she had the moves. Her jitterbug was crisp.

Ace was the kind of kid that other people described as too smart for his own good. He often lost track in school, and not because the subject matter was difficult. Just the opposite. Ace demolished logic problems, equations, and word problems with ease, leaving plenty of time for his attention to drift. He would often check out of class entirely and focus on reading or doing something else, forever frustrating his teachers. His grandma understood him, though. She was smart when she was a kid too, and was more than ready to go to the mat for her late daughter’s son whenever the school called with a complaint.

The ghost switched to the twist after a while, and Ace quietly appreciated how funky she got with that one too. She started out kinda basic, but then got on one leg and got a little low, throwing in flourishes with her arms…no, he couldn’t get caught up in whatever this was going to end up being. He couldn’t play her game. His eyes flicked back to his Nintendo and he kept playing, slowly cranking the volume up on Zelda so he didn’t get distracted.

An hour later, Ace decided that the word for the ghost was “relentless.” She did the jitterbug, the twist, and half a dozen more moves back-to-back-to-back, only pausing between dances to rhythmically sway while she caught the next beat or decided on the next dance. He wasn’t sure which. Maybe she had a ghost boombox he couldn’t see, or was reliving her past.

He finally lost his patience when she hit the Roger Rabbit over by the dresser. Ace hit the save button, put the console to sleep, turned over on his back, looked up at the ceiling, and sighed loudly. “What,” he said, “do you want?”

The ghost stopped in her tracks, slowly shifting back to standing normally. “I knew you could see me! You’re sneaky, daddio.” She clapped her hands, and the sound was disconcertingly quiet. “They said you was smart!”

“They who?”

“You know. All types of folks. I heard some living cats talking about you the other day, so I asked around some of us non-living folks too. Everybody called you real smart. Maybe even a genius. Cute as a button too. But old man Phineas, he said you had helped his great-great-grandson out of a jam, and I should definitely come to you with my question.”

Ace scoffed. “Geniuses are fake.” He thought about it a moment, and then sat with his legs hanging off the edge of the bed, dangling just above the floor. “But thank you. I don’t know no Phineas, though. Who’s he? And who is he to you?”

“Oh, he’s dead like me. He’s one of the oldest one of us out there, so he kinda keeps an eye on us young ghosts. His grandson is named Philip though.”

“What do you want from me?”

“I want you to solve my murder.”

He frowned hard, wrinkling his nose and furrowing his brow. He looked at his window, then at the floor, and then back at the ghost before his face untwisted. “Okay. I gotta eat dinner first, though.”

“G’head. I got all the time in the world.” She tapped a toe three times, and launched into another dance.

—

After dinner, Ace grabbed a notepad and pencil out of his bag, sat cross-legged on the floor next to the ghost, and got to work.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

The ghost giggled. “Guess.”

“No.” Ace glared at her.

She frowned. “Okay…I’m Shelly.”

“Okay. Shelly.” He wrote it down while he spoke, stretching out the both syllables of her name while scratching them into the paper. “You know when you died?”

“Not the date, no. The whole day is kinda blurry, honestly. I remember going out to a party and then…just waking up somewhere else and being able to walk through walls. I don’t even know how much time has passed, really. Every day just kinda blurs when you’re…this,” Shelly said.

Ace nodded, sympathetic. “Got a last name?”

“Simmons.”

“With a D?”

“Nah. Oh-en-ess.”

“Okay.” Ace scribbled a bit more. He’d started separating his page into boxes of different sizes. One box held her name, height, weight, and other personal details. “You remember where it was?” he asked.

“Where what was?”

“The uh…the incident.”

“Oh, you mean me getting killed? It was at a party.”

“A costume party?”

Shelly startled, her eyes going wide. “How’d you know it was a costume party?”

“‘Cuz I ain’t never heard of no flapper knowing how to do the Roger Rabbit, that’s why.”

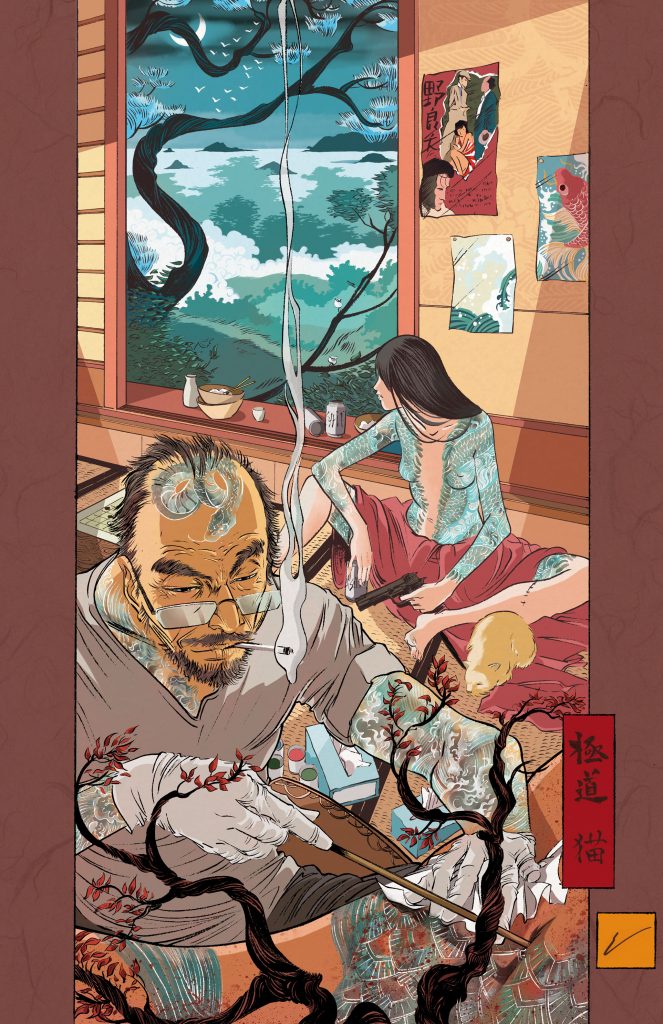

Shelly laughed again, deep and long, her mouth wide open. “I knew you were smart.” She covered her mouth and tittered a little more for good measure. “It was a costume party. The whole thing was Harlem Renaissance themed. I worked really hard on mine. I can’t believe you saw through it. Uh, so to speak.”

“I didn’t. The costume is really good, but it was the dancing that gave you away. And you don’t really sound like you’re from then, even when you try to sound like from then.” More scribbling. “The party was uptown? Who else was there?”

She broke down what she remembered of the party—who hosted, how she got there, and what the party was like. Ace took enough notes to fill three pages, pausing occasionally to flip to a different page and ask clarifying questions.

By the end of it, he had a good picture of what he was looking for. Shelly Simmons woke up dead one day at least ten years ago, maybe even twenty or thirty, stuck forever looking like a seventeen-year-old flapper because of the circumstances of her death. She suspected she was murdered, even though she didn’t have any wounds to indicate her cause of death, and she had a good idea where it happened, though not the exact address. Ace asked Shelly to walk him there and show him around while he investigated the area. There may be clues they could find, or people they could talk to who remembered her.

That was a job for tomorrow, though. It was getting late, and Ace had learned a hard lesson about sneaking out of the house on nighttime adventures already.

—

The next morning, as they walked out Ace’s front door (Shelly phased part of the way through it, which was disconcerting), Shelly said, “Soooooo,” and paused for a while before continuing. “How come you ain’t afraid of me?” She gestured at herself, half-Vanna White, half-wiggly ghost fingers. “With the ghost thing, and all that.”

Ace popped his teeth at her. “What’re you gonna do? Read Langston Hughes at me in a devil voice? Make me dance until I died?” He walked alongside her at a New York pace with his eyes locked on his phone while he typed and swiped. “I figured you spent so much time dancing instead of haunting me that you weren’t gonna hurt me.”

Shelly laughed again. “I just might make you dance, player! You seen the end of Beetlejuice?”

He ignored her and said, “I got one too. A question. How come you ain’t haunting the place where you died?” He must’ve found something he liked on his phone, because he grinned, gave it one last swipe, and locked his phone before tucking it into a pocket. “Isn’t that how ghosts work?”

She was quiet for a moment. “Most of us just kinda wander around, to be honest. The ones that are trapped in a place, like they can never leave or nothing like that? They give me the willies. It’s all anger and pain with them. No fun. Most of ’em can’t even talk. Just hollering all the time.”

“You think you’d remember what happened if you were more mad about it?” Ace asked. “You seem like you’re taking it pretty well.”

“Yeah, I am now. You shoulda seen me when I woke up though.” She patted her hair into place, a pantomime from back when she had physical form. “I’m just curious about it nowadays, really. I heard about you and figured why not ask, see what’s up? I’m just lucky you can see ghosts. Most folks can’t.”

The blocks they walked were long ones. Ace was always struck by how quickly the city changed modes. His apartment was in a decent-not-great area, but just two blocks away was an expensive grocery store with a majority white clientele. Three blocks out, a virtual reality fitness studio. Four blocks after that, there was a corner store that he figured out was a money-laundering enterprise when he was eight years old. (They kept his picture behind the register and banned him for life. It was still there, as far as he knew.)

Every few blocks, the city took on a new personality. He loved it.

Ace knew his corner of the city well, but a short distance into their walk, he realized Shelly knew it as a different neighborhood than he did. She explained that she grew up nearby too, and that the grocery store they passed used to be a rink where all the kids would gather to bounce, rock, and roller skate. The rink was owned by a young couple. He sold dope and she did hair, at least until they saved enough money to lease the building, renovate it, and open Figure Eights together. Afterward, she only did her daughter’s hair and he sold dope out of the manager’s office.

Shelley said that for the first couple weeks, boys from one crew would go and fight boys from other gangs inside the rink itself, ruining parties and getting the cops called on everyone. It was a free-for-all until the owners hired a couple people they knew from running the streets to serve as bouncers.

Even though one bouncer was black and the other was Samoan, they could’ve passed for siblings. Even setting aside their similar physiques—Shelly said, “Them boys was big, like the whole Earth squeezed into a blue Polo,” and stretched her hands wide—they’d grown up together, in a way. Shelly explained that they had attended rival schools ever since sixth grade, and met each other on the football field a few times a year, at which point they did their level best to kill each other. Their relationship started out as beef but evolved to a genuine respect, then appreciation, and finally friendship. Neither of their schools ever had a chance of winning state, anyway. When their football careers came to an end, they turned to hustling, and when that got too hot, well, bouncing was easy for a big guy and dead simple for two big guys.

It turned out the VR gym had been a trendy spot back in Shelly’s day, too. Way back then, it was a martial arts studio. Some old GI had come back from Vietnam with a whole passel of half-hearted martial arts moves and half-baked philosophy, moves that were quickly passed on to several neighborhoods’ worth of knuckleheads. He eventually hired actual martial artists to lead his classes and tightened his game up, but Shelly still talked about the studio like he was selling snake oil.

Their trek across the city was punctuated with several stories like this. Parking lots that used to be bookstores, high-rise apartment buildings that used to be a cluster of townhouses for up-and-coming families, and boutique brunch spots that used to be restaurants that could make a whole block smell like barbecue and fried chicken if you walked past at the right time. Shelly talked about the past like it was still happening somewhere, and Ace soaked up her knowledge as best he could. You never know.

—

“Why do they call you Ace, anyway?” Shelly asked after a while. She was running out of stories to tell, and the haziness of some of her memories surprised and unsettled her.

“It’s what my mama named me,” Ace said.

“Yeah, but is it short for anything?” Shelly had taken to walking backwards for fun, just ahead and to the side of Ace, so she didn’t obstruct his vision. She never looked behind her, instead phasing right through every person, sign, and patio that a living person would’ve tripped over. She was showing off, really. Trying to impress the kid. “Like a family name?”

He thought for a minute. “I don’t think so. It’s not short for anything, either.”

“Harlem, though,” she said. She said Harlem again, hitting the Har extra-hard. “That’s a name for real. You from New York?”

“Born and raised, least before Mama died and I moved here.”

Shelly snickered. “More like born and born. You ain’t near raised yet. That’s your real last name too?”

“Yup. My mama picked that too. Said my daddy wasn’t worthy and that I needed a stronger name. After she passed and Grandma took me in, Grandma changed her name to Harlem too. She from Mississippi though.”

“You got a cool name, youngblood.”

“Yeah,” Ace said. “I know. That accent you keep doing still sounds fake, though.”

—

About three blocks out from where Shelly remembered the party taking place, Ace went quiet. Shelly watched his body language change, becoming much more closed off and tight. He gripped the straps of his backpack while he walked, his head rapidly panning from left to right as they made their way.

Shelly didn’t say anything at first, but as he began walking slower and slower, she finally got up the guts. “What’s wrong?” she asked. “You okay?”

Ace didn’t answer and kept looking around. Finally, he said, “You said angry ghosts haunt people. But can you do that stuff too? Scaring people, like in Poltergeist?”

“I…don’t really like to do that. It brings bad vibes and worse sometimes. That’s how we get trapped on Earth.”

“So I can help you, but you can’t help me?” Ace muttered, and a bit more that Shelly couldn’t catch. She frowned and stopped cold. Ace made it three or four paces ahead before he realized she’d stopped, and he turned to look back at her. “We can’t stop here,” he said. “Saul lives around here. We just passed his house. I gotta keep moving.”

“Who is Saul?” Shelly asked. Ace looked at her, his face blank, and she figured it out. “Ahh. I’m sorry, kid. Bullies are no fun. He goes to your school?”

Ace nodded.

“Okay. I didn’t know he lived around here. I’m sorry, kiddo.”

Ace snorted. “I’m not a kid. I’m thirteen. I’m just waiting on my growth spurt.” An older woman passed him as he said this and looked back, wondering who the heck he was talking to while walking around alone. But she figured it wasn’t her business, so she kept it moving.

Shelly moved to reply in her usual mode, but refrained. She could tell the kid was hurting. “Look,” she said, “I can’t haunt him or whatever. It doesn’t really work like that. I’m really sorry, Ace. I wish I could help.”

“Can other people see you?” Ace asked.

Shelly shook her head. “Only when I really want them to, and even then, they have to be, uh…whatchacallit…sensitive. I didn’t think you could see me at first, but I had a hunch…”

“Can you move stuff?”

“Like physical stuff? Banging on pots and pans and all that? Nah, that’s not really what we do either. Those angry ghosts, yeah. They do it all the time.”

Ace picked up the pace. “Can people hear you? Like, can you talk to them or something like you’re talking to me?”

“Yeah, I think so. Sometimes, anyway. Most people just think it’s the wind or something, I dunno. I think people don’t wanna hear us, nine times out of ten.”

He stopped and looked dead at Shelly. “If we see Saul, can you say something to him for me?”

“What do you want me to say?”

Ace told her.

“What’s that mean?” Shelly asked. “Why do you want me to say that?”

A shrug. “I want you to say it because I think it’ll work. And either you say that or I get my butt beat again after walking all the city with a ghost who doesn’t even know when or where she died.”

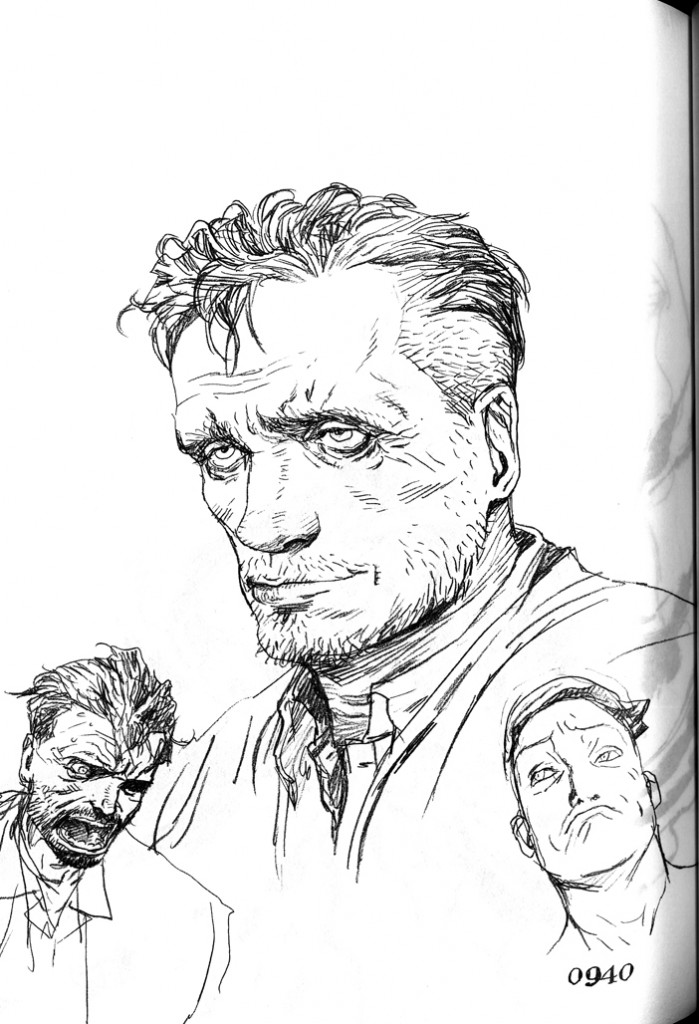

Like a bad joke, at that exact moment, Saul himself turned the corner. Unlike Ace, he’d hit his growth spurt early, and stood nearly six feet tall already. He was slim but wiry, built like he was born to play basketball. He was wasting his physique by sticking kids for their lunch money and belongings, but he didn’t know any better yet. Plus, easy money is easy money. He smiled wide when he saw Ace and leaned forward with both hands in his pockets. “Well, well,” he said. “Ace Harlem!”

Ace sighed. “You need to get the heck on, Saul,” he said.

Saul leaned back in mock surprise. “Little mouse boy got a voice now, huh?”

“I got more than a voice,” Ace replied. “And if you don’t back up off me something bad will happen to you.” Ace tried to lock eyes with his bully to really show him he meant business, but found that his eyes couldn’t help but wander.

“What’s a mouse got to tell me?” Saul theatrically cracked his knuckles and started stretching. “You gonna throw some cheese at me, mouse? Gonna nibble at my toes?”

Ace breathed in, and then out. He looked at Saul’s chin, still unable to meet his gaze, and waited. “Listen,” he said.

Saul smiled at him, a deeply predatory grin, and opened his mouth to speak. Instead, a surprised look crossed his face. His jaw dropped open, he looked a little away from Ace, his face crumpled like it was in slow motion, and tears began to stream down his face.

“If you step to me again,” Ace said, really feeling himself now, “I’ll make it worse. I swear.”

Saul lurched forward with a fist raised, ready to knock Ace into the next county, and stopped, his eyes blurry. He lowered his fist and walked straight past Ace. He didn’t say a word until he got home and flopped face-first onto his bed.

“Well dang!” Shelly said after he walked away. “What did all that mean?”

“It doesn’t mean anything if he beats me up again. But it might get me some breathing room for a bit.”

“Yeah, but what’s it mean?”

Ace frowned. “People keep telling me I’m a genius, but I’m not. I just pay attention. And paying attention means I learn things that other people don’t want me to know. Everybody has secrets.”

“You couldn’t tell him all that yourself?”

“The last time I tried to say something smart to Saul, he knocked out the last of my baby teeth.”

Shelly pursed her lips and nodded. “Fair ‘nough. I kinda feel like I just did something really messed up, watching old boy fall to pieces like that.”

“More or less messed than throwing my backpack onto a ship passing under a bridge with all my books in it? And then throwing me into the river right after it?”

“Hmm. Less. For sure.”

—

The place where Shelly died was still standing after all. It was a tall, dilapidated building, an old apartment complex that was about six years late for demolition. All of the glass in the windows of the first two floors was gone and the front door was hanging from the top hinge. The door was covered in graffiti where it hadn’t been scorched. The grass was brown and stiff, with a light coating of litter. A stray cat perked up when they walked by and then went back to sunning itself on a rotting old tire.

Shelly and Ace looked up at the building and then at each other. “Well,” she said. “Here it is. Home sweet home.” She looked equal parts sad and expectant, and laughed nervously. She watched Ace kick at the dirt, shade his eyes while he looked up at the building, and eventually turn away without going inside.

“We should go,” he said. “Ain’t nothing here.”

—-

They spent the next leg of their trek in silence. It took about thirty minutes as Ace retraced their steps back toward his neighborhood while looking for an intersection he wanted. When he found it, they turned left and walked until they found the bookstore Ace had been planning to go to. He opened the door for Shelly without even thinking about it, and the bell over the door rang a chime he’d heard hundreds of times before.

The man behind the counter grinned wide when he saw Ace come in. He winked and flicked something at Ace’s head. Quick as lightning, Ace snatched it out of the air and looked at it. “Hi, Mister Washington,” he said. It was a short and thin stick, like a candy cigarette made of light brown wood.

Shelly looked on, bewildered. She felt like Ace had given up on his search entirely.

“Fresh out,” Mister Washington said. “I remembered you saying you didn’t know if people were gonna be into my chewing sticks without adding some serious flavor to it, so I been in the lab all week, cheffing up something good. That one’s cinnamon, but I put a hint of cayenne in that to give it some bite. I got a sea salt one too, but I ain’t perfected it like I have that one just yet.”

Ace bit down on one end of the stick, holding it with his lips like he’d seen old-timey actors do with cigarettes. “‘Preciate it.” He waved and walked to the rear of the store, through a hanging barrier of red, black, and green beads, and then down the stairs at the back. “The library is down here,” he said out loud for Shelly’s benefit, but not loud enough for anyone else to hear. “I just want to see something.”

“That’s fine,” she said.

Downstairs, Ace found Missus Linda Washington, the founder and owner of the bookstore and mother of the man at the desk. They greeted each other and Linda clasped his hands, happy to see him. They chatted a bit, and then Ace asked for something that made her beaming smile turn down slightly. She pointed, and watched him amble over to one dark corner of the library.

“What are you doing?” asked Shelly. “I thought we were going to investigate…to solve my mystery.”

“There was nothing at that building,” Ace mumbled. “It was old and run down and any evidence woulda been long gone.” He set a huge book down on a table, wiped the dust off the cover, and started flipping through. “No point to it.”

“Stumped you, huh?” Shelly dragged a finger through the dust wafting through the air, watching as it passed through her hands. “It’s okay. I know it was a long time ago.”

“Sorry, can you give me a bit?” Ace asked. “Can you wait upstairs? I need to concentrate.” He kept his face buried in the book while he spoke, flipping pages quickly but carefully. “Just like an hour, maybe.”

Shelly’s nose wrinkled. “Okay.” She hopped in place, and then after a second bounce, jumped up to the first floor and out of Ace’s vision.

He kept turning pages.

—

About forty-five minutes later, Ace said goodbye to the Washingtons and left the store. He found Shelly sitting on the curb a few feet away, and plopped down beside her, his feet resting in the gutter.

“So,” Ace began. “I googled you when we left the house.”

Shelly looked at him, unimpressed. “You did what?”

“I googled you. Uh, it’s like a—”

“No, you big dummy. I know what Google is. I’m dead, not dumb.”

“Oh. Sorry. I don’t know if ghosts have internet or things like that, so I just…anyway, I googled you. You gave me plenty of details at home, so I just did it when we were getting ready to go. And…well, you didn’t get killed, not exactly. But you did die. I guess that’s obvious.”

“So what happened, then?”

“Well, at first, I found a news clipping online that said you overdosed at the party. But there was something fishy about it, like it had just been assumed that’s what happened. The details were missing or wrong, you know? It didn’t add up.” Ace knocked the back of his shoes against the curb and hugged his knees after. “I wanted to see more, and figured I wouldn’t find it online. So I checked Missus Washington’s library. I found another article that said you had actually just had an allergic reaction to something, peanuts or something like that, they said. Probably wasn’t a bee sting. Your friends there tried to bring you back, but I guess you were there and laughing and then you…like…weren’t.”

A long line of taxis passed, and Shelly watched them speed by while she processed this new information. Ace sat next to her, quiet and awkward. She finally looked up at the sky, exhaled, and laughed hard. She flung herself back so recklessly that Ace reached out a hand to catch her before she hit the sidewalk. He drew his hand back when she passed right through it. She kept laughing, even as she sunk into the sidewalk a little bit. She gripped her stomach and rolled over, Ace watching her back while she laughed until she hitched and dry-heaved.

“Peanuts!” she said after a moment, while Ace wondered how a ghost could catch her breath. “I hated ’em as a kid. Can’t believe they’re what killed me.” She sat back up, still breathing hard. Instinct, maybe? “I thought maybe I got serial killed or something like that, but peanuts? Whew.”

Ace laughed a nervous, halting little laugh too. “The bookstore had your obituary, and I figured that since Missus Washington keeps copies of every black newspaper in town, she might have some more info on you in her archives. I didn’t find much, though. Just that article in one paper, and your obituary in another. I took a picture of your obituary if you wanna read it. It says your auntie wrote it. It was a poem.” He fished his phone out of his pocket and moved to unlock it.

“No, thanks,” Shelly said, holding out a hand. “If it’s the auntie I’m thinking about, she was always trying to be the center of attention anyway, even before she started writing bad poetry. Man. Peanuts. You really are a genius, you know that?”

“Geniuses are fake,” Ace said. “This was just logic. Most things make sense, if you look hard enough. Even the random stuff. There’s always some kinda order. You just have to look around hard enough to find it.”

“Is that right?” Shelly asked. “Well, all that still sounds pretty smart to me.”

Ace mumbled a thank you and looked down at his dirty shoes.

Shelly watched him for a moment. “You got any friends, ki-sweetie?”

“I got plenty of friends,” Ace said. “And ‘sweetie’ is actually worse than ‘kid’.”

“Well,” Shelly said. “Ace Harlem, you just got yourself one more friend.”

Ace fished another chewing stick out of his bag and popped an end into his mouth to hide his smile. The two of them sat there chatting until the sun started going down and Ace had to mosey his way home.